In 1967, astronomers at the Observatoire de Haute-Provence in the south of France discovered potassium flashes while they were observing stars. But the laws of physics that were known at the time didn’t provide any explanation as to how a star could produce these flashes. Were there aliens trying to communicate with us?

Light is made up of several colors and can be split up into each of these colors. When you split light into its constituent colors, you end up with a spectra. This is what happens when you see a rainbow: the light from the Sun is split into different colors by drops of water.

If you look at the colors a light is made of, you can figure out a lot about the thing that produced the light. Each atom emits one or more very specific colors in certain conditions. For instance, sodium emits yellow light, and mercury can emit blue light.

Instruments that decompose light into each of its colors is called a spectrometer, and these instruments are very useful in astronomy. This is because measuring the spectra of a star tells us – among other things – what atoms can be found in its outermost layers.

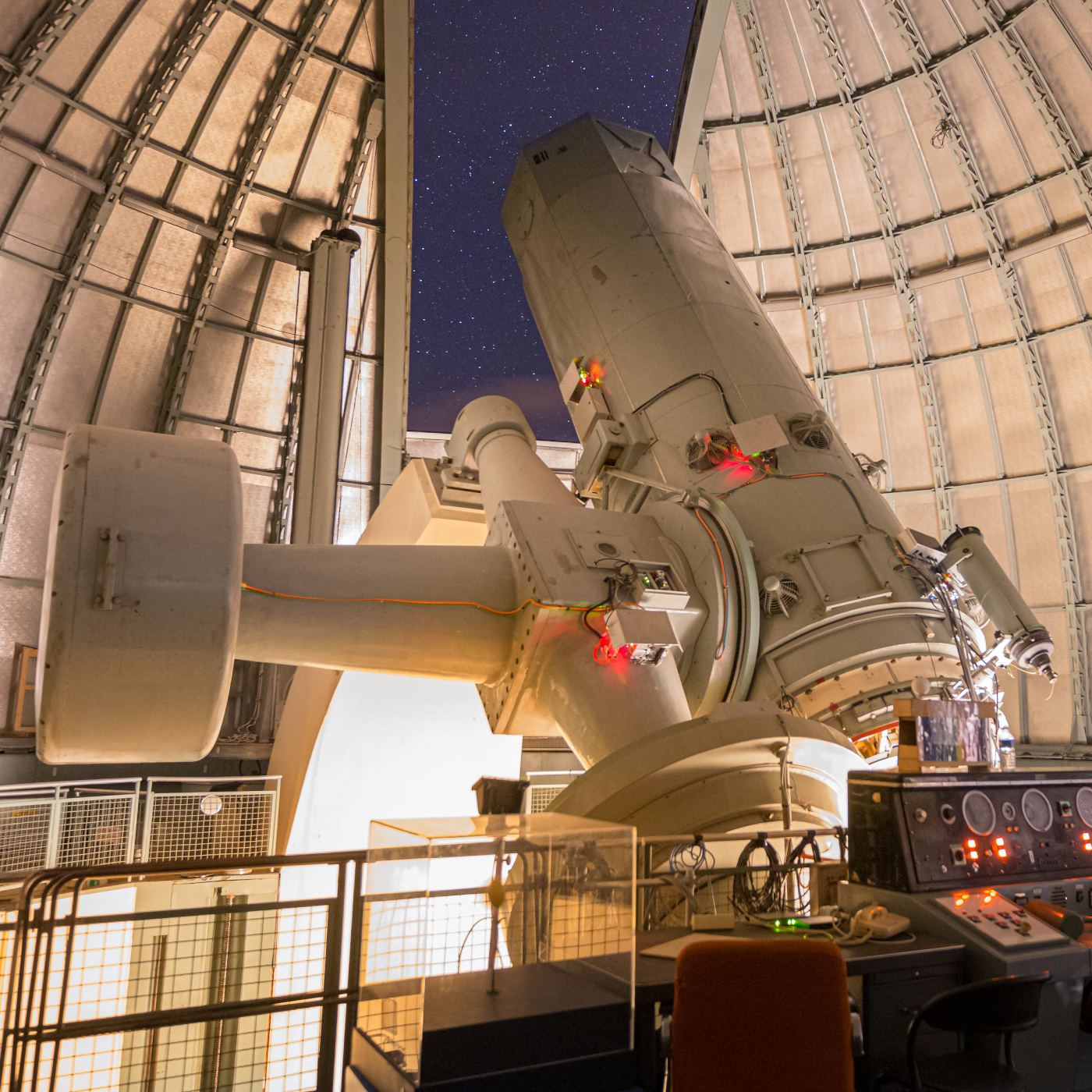

At the Observatoire de Haute-Provence, in the town of Saint-Michel l’Observatoire, there is a telescope equipped with a spectrometer. In this observatory in 1967, while the spectra of a star was being measured, this spectra suddenly changed. Now, the spectra of a star can change for all kinds of reasons: something (like an exoplanet) passing in front of the star, dust being ejected, a change in the reactions at the heart of the star,… But nobody had ever seen a spectra change like this: the color associated with potassium suddenly appeared very brightly and for a very brief amount of time. This kind of variation is called a potassium flash. And at the time, astronomers had no idea what could be causing these potassium flashes. So of course, they went out to try and solve the mystery.

Potassium flashes were observed in two other stars at the Observatoire de Haute-Provence. But astronomers still didn’t know what was going on in these stars. To try and understand how and when these flashes occur, astronomers decided to semi-automatically measure the spectra of 126 very bright stars and see if they could find any other potassium flashes.

But they didn’t find a single potassium flash in any of these 126 stars. It was rather uncanny that 3 stars with no apparent link would have potassium flashes, but 126 other stars wouldn’t have any. And astronomers still couldn’t find a physical explanation for these flashes. Nor could they explain how so much potassium could end up around a star.

The astronomers did various experiments, and finally noticed that if you light a match at a certain spot in the observatory, and if the telescope is oriented in a certain direction, then the spectrometer picks up a potassium flash, just like those that were measured while observing stars. Several brands of matches were tested and all gave the potassium flashes. It became plausible that the flashes weren’t caused by the stars, but rather by something happening on Earth. And it clearly wasn’t aliens.

Turns out, someone at the observatory would light a smoke in the middle of the night while observations were going on. And sometimes, they would light their cigarette at the right spot in the observatory for the potassium flash from the match to appear in the spectrometer.

So the flashes weren’t actually some new astrophysical phenomenon, but rather a terrestrial phenomenon that masked part of the star’s spectra. And most importantly, the spectra in which these flashes appeared couldn’t be used to study stars, because the spectra of the star was hidden behind the spectra of the match.

There is very little light emitted from stars that gets to us. So when we do astronomy, we have to get as far away as possible from the lights generated by humans. That’s why astronomical observatories are built far away from cities. But with upcoming satellite mega-constellations like Starlink, even the most remote locations on Earth won’t be protected from the light reflected by satellites, because satellites can be much brighter than celestial objects of interest. Observatories are already impacted by this new kind light pollution, with observations rendered unusable because of the unexpected passage of a Starlink satellite in the telescope’s field of view. Just like with the potassium flashes, this is some human activity that is keeping us from looking at the stars.